By Imelda V. Abano

From their vantage point at Manila Observatory, scientists have monitored changes in temperature and rainfall that have altered life in the Philippines. But they also have watched changes due to human actions—land-use, building, and development decisions that have made people more vulnerable to extreme events, like Typhoon Haiyan.

Antonia Yulo Loyzaga, executive director, talked about the Observatory’s work, which was to be featured Thursday at the Powering Progress Together forum in Manila sponsored by Shell.* Loyzaga discussed her colleagues’ work in helping to improve understanding of the new weather and geological hazards the nation faces, and how cities and communities can reduce their risk in a changing climate. (See related “Quiz: What You Don’t Know About Climate Change Science.”)

The Observatory collaborates on climate and disaster risk reduction with the International Council for Science, the International Development Research Center, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Asian Disaster Preparedness Center, and other agencies. Recently, Loyzaga headed a logistics coordination and situational awareness support team for the Armed Forces of the Philippines’ Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response effort during Typhoon Haiyan. (See related, “Q&A With Philippines Climate Envoy Who’s Fasting After Super Typhoon Haiyan.”)

Loyzaga also leads the metropolitan Manila team of Coastal Cities at Risk (CCaR), an international project aimed at building capacity for climate change adaptation in five coastal megacities. She is a member of the Science and Technology Committee of the UNESCO National Commission and represents the Manila Observatory on the Philippines Department of Science and Technology’s Committee on Space Technology Applications.

We had a conversation by email before her speech in Manila.

Tell me about the role of the Manila Observatory.

[It] is a scientific research institution focused on transforming development through evidence-based solutions. We were established [in 1865] principally to try and understand the impacts of changes in climate, weather and geological hazards on populations in this area of the Pacific region.

Then, as now, many of these settlements were in coastal areas or along riverbanks, in order to gain access three basic resources: food, water, and energy. Urbanization in this century has created coastal megacities that radically altered land cover [and] land use, as well as the ways we use sources of inland, coastal, and marine waters. The local ecological footprints of these cities have global impact. Their emissions fuel the engine of climate change. And rapid unregulated urban growth has, in turn, led to environmental changes that have altered land-ocean-atmosphere interactions.

For populations in developing countries such as the Philippines, urban growth has not necessarily meant sustainable development. In some megacities, such as Bangkok, Manila, or Lagos, biogeophysical and social complexity threatens their resilience to disasters. At the Manila Observatory we seek ways by which a dynamic and systematic understanding of climate change, disaster risk, and human development can decrease exposure and vulnerability, and pave the way for inclusive growth.

What is your message on poverty and disaster risk?

Policymakers and the general public need to embrace the value of good science in making development decisions. Investment in infrastructure, social services, and environmental analysis cannot be divorced from each other. Understanding their complex relationships, formulating integrated solutions, and developing institutional capacity to implement these are essential to moving forward together. It has been said that risk reduction is about having the right information in the hands of the right person, at the right time. We should add: This person and the affected population also need the right tools, technologies, systems, and the political will to accept and use them.

How vulnerable is the Philippines to the impacts of climate change?

As of 2012, the Philippines continued to rank third in the United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security’s list of countries most at risk of disasters. Given [typhoons Bopha] and Haiyan, we do not expect our ranking to improve in 2013 and 2014.

We are an archipelagic country with a declared government policy that supports the urbanization of coastal cities in order to spur economic growth. (See related “Quiz: What You Don’t Know About Cities and Energy.”) Hyperconcentrating people and economic resources in coastal areas—without investing in the institutional capacity to build a shared understanding of the science of integrated risks from climate change and geological hazards—is a recipe for disaster.(See related, “5 Reasons the Philippines Is So Disaster Prone.”)

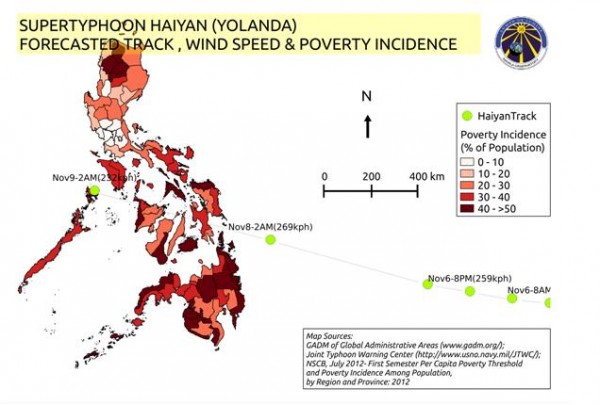

The Philippines is rapidly becoming an urban nation with most of its population [living] on floodplains or coasts. We are situated along the Ring of Fire and face both the Pacific Ocean and the West Philippine Sea. The heating up of these bodies of water generates tropical cyclones and monsoon rains. Unfortunately, poverty has not decreased significantly in the last decade and migration to peri-urban areas is seen as the pathway to a better future. When combined, extreme weather, increases in population density, and the persistence of poverty constitute the essential ingredients of a disaster.

What lessons can be drawn from Typhoon Haiyan?

The last two reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change emphasized the development-related links between hazards, exposure, and vulnerability. These three elements constitute disaster risk. The reports also state that extreme weather events are more likely to occur due to the failure to decrease emissions which fuel climate change. While Haiyan taught us many lessons, these are the ones that I believe stand out:

Understanding the hazard before it strikes; what is exposed and why you are vulnerable are essential to reducing risk and saving more lives. The physical forms, dimensions, and location of coastal areas influence the ways the ocean will impact settlements when waves from extreme weather and tsunami strike.

Risk communication is not hazard communication. Early warning must also be in the voice of the vulnerable and not only in the voice of the hazard scientist. When it comes to saving lives, understanding the science of hazards beforehand, can be just as important as understanding its possible impact. Even if no one knew what a storm surge was, if they understood that its impact on them would be just like a tsunami, would more have been able to respond correctly to the warning?

Informed collaboration, coordination and clear lines of authority are imperative. To quote the New York Times’ Dot Earth blogger Andrew Revkin, “Complexity + Complacency = Calamity.” We need to ask the question: Given the amount of government and international support, could there have been a systematic, science-based search and rescue operation to save those who had been buried alive?

What more should have been done on weather warnings, as well as on recovery?

A disaster expert involved in Haiti told a group of us recently, “Nothing changes, until behavior changes.” This means that risk reduction and climate change adaptation are essentially social achievements. The Manila Observatory’s archives show similar disasters occurred in the places struck by Haiyan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. To paraphrase the current buzzwords, had we built back better elsewhere after each one, would Haiyan have been a catastrophe?

In developing countries, where poverty is a form of persistent vulnerability, resilience does not mean the restoration of a community to its former state. Rehabilitation and recovery must therefore be risk-sensitive. Livelihoods can be the sources of survival and the drivers of exposure and vulnerability at the same time. Reconstruction, which is the most tangible investment in recovery, cannot be equated with dividing up land into disconnected parcels of physical planning and development. Where informality is historically present as a socioeconomic and physical pattern, rehabilitation and recovery necessarily means education, institutional social change and a program of inclusive redevelopment.

How important is science in managing risks and environmental impacts?

The Society of Jesus established the Manila Observatory in 1865 in order to serve the Filipino people through scientific excellence. At the cusp of our 150th year, this mission has not changed.

Scientific knowledge and research are essential building blocks of sustainable development. While there have been advances in technology far beyond what our founders could have dreamed, the fundamental challenges facing the Philippines and the rest of the world are essentially the same: Where do we find energy, water, and food to support a humane existence for all?

Our world can sustain us only if we constantly strive to understand the scientific relationships between space, our atmosphere, land, oceans, and people, and learn how to engineer inclusive decisions about our global future. Our hope for the Philippines is that with the right formula for investment and collaboration in scientific research, our hazard-prone country will become the showcase for how science can truly transform development.

Imelda V. Abano, founder and president of the Philippine Network of Environmental Journalists, is reporting from Manila.

*Shell is sponsor of National Geographic’s Great Energy Challenge initiative. National Geographic maintains autonomy over content.

Write-up from National Geographic